Intentionality and Cultural Evolution - Towards a Generalized Learning Theory Account

| Back to Essay List | Modified: 23 Jul 2020 | BibTeX Entry | RIS Citation |

(the following is a continuation and completion of a post begun in 2013, stimulated by a recent article by D.S. Wilson)

Among those who object to framing cultural evolution as a Darwinian theory, one of the most important reasons for objection is the evident importance of intentionality in human behavior (and among many animal species). Liane Gabora has perhaps been one of the most persistent advocates that while culture evolves, it does so by mechanisms other than natural selection, since natural selection requires variation to be “random” (Gabora 2013).

Generation of Variation in Darwinian Processes

Or does it? Lipo and I argued in response that most modern commentators are overinterpreting the term “random” in the core Darwinian paradigm: that the generation of variation is merely causally unprivileged with respect to the differential persistence of that variation (Madsen and Lipo 2013). David Sloan Wilson, in a recent and very clear article on intentional cultural change (Wilson 2016), makes the same point very crisply:

In the standard portrayal of genetic evolution, mutations occur that are arbitrary with respect to their consequences for survival and reproduction (fitness). Those that enhance fitness increase in frequency until they become species-typical. The word ‘arbitrary’ rather than ‘random’ in the previous sentence is deliberate. If a mutation is random, then it results in a new phenotype that deviates from the previous phenotype in any direction with equal probability. The standard portrayal of genetic evolution does not assume that mutations are random in this sense. Instead, the assumption is that mutations do not anticipate the phenotypes that are favored by natural selection. This is the meaning of the word ‘arbitrary’.

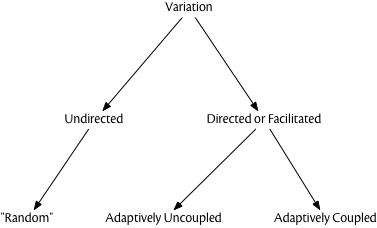

In fact, we can look at variation-generating mechanisms along several dimensions, as shown in this diagram. Variation may be “undirected” or “directed.” Directed variations are innovations or errors that occur when a variation-generation mechanism targets specific components of the genome or cultural repertoire. In contrast, undirected variations are errors or innovations which occur in some random component of the genome or cultural repertoire.

The classic example of undirected variation is the cosmic ray streaking through a cell nucleus, causing damage to DNA which results in “flipping” one or more nucleotides during the repair process. This is the archetype for what nearly everyone means when they talk about “blind variation” in Darwinian evolution. In cultural evolution, a person copying an artifact will make motor and perceptual errors in copying, which are often random with respect to which physical dimension they occur upon (Eerkens and Lipo 2005).

But we now also understand that there are many mechanisms whereby variation can be generated in a “directed” fashion. Environmental stress seems to have a variety of effects on the rate and location of mutations in the genome, and there are a variety of epigenetic mechanisms whereby temporary changes in gene expression can be inherited by the next generation, and thus permanently affect a lineage.

The important thing to understand about such “directed” mechanisms for generating variation is that while they are targeted, they are unprivileged with respect to knowing how selection will ultimately filter the results of their generation. Causal arrows run one direction, and variation is always generated before selection affects the frequency of variants. Genomic mechanisms which increase the mutation rate in selected regions of the genome are certainly the products of past selection, but there is no causal arrow which gives them information about how the results of their action will fare in future survival and reproduction.

And this, really, points to the way out of the issue. There is simply no requirement that variation be “random” with respect to…anything. The generation of variation is simply causally uncoupled, or unprivileged, from the “judging” of its fitness or utility down the road. The “two step process” of Darwinian evolution is defined by that uncoupling.

Intentionality

Which leads us to the thorny issue of “intentional” behavior in a mechanistic, Darwinian theory. My mentor, Robert Dunnell, was vehemently opposed to the inclusion of intentionality in any scientific theory of cultural change, for a variety of reasons which were correct. Mostly, the objection to intentionality is the causal role it plays in most social sciences, short circuiting the “two step” process and asserting that change is often a “one step” process whereby people perceive a problem, choose the best solution to deal with it, and implement that solution. Theories built on this kind of logic include variations of rational actor models in economics, overly simplistic versions of adaptationist evolutionary ecology, public choice theory, and of course a long list of unilinear, progressivist, vitalist, and Lamarckian models of cultural change in anthropology. All of which have been instrumental at various times in preventing us from constructing testable, scientific accounts of cultural change.

Which presents us with a seeming conundrum. Clearly, humans and many animals exhibit behavior which is “intentional,” and we and other species evolved this capability over a broad span of time (given its taxonomic breadth) by natural selection acting upon variation generated by various directed and undirected mechanisms. But equally clearly, intentional behavior cannot be a “shortcut” around the two step process of variation and selection, since like all other variation, our intentions and strategic planning are causally prior to the outcome of their expression, and often long prior to their downstream affects on our reproductive success, survival, and our ability to spread our ideas and cultural norms.

In his recent article, David Sloan Wilson (Wilson 2016) discussed a number of mechanisms by which intentional behavior has probably evolved in humans and other lineages. The adaptive nature of the vertebrate immune system, for example, is a paradigm example of an adaptive, open-ended process; it is, in fact, a selection process within a selection process. Wilson also describes operant conditioning and explicit decision-making.

It is worth trying to give a general account of such mechanisms, however, because it may be possible to unify many kinds of “directed” variation mechanisms, including those involved in intentional behavior, and understand what they share in common. The natural framework for unifying such examples is statistical learning theory, which attempts to describe a generalized framework whereby accurate models can be inferred by exposure (in some fashion) to data (Kearns and Vazirani 1994).

It is becoming somewhat fashionable to make connections between learning theory and directed mechanisms in evolution (for example, see (Power et al. 2015) ) after the recent book by Leslie Valiant, one of the founders of formalized statistical learning theory (Valiant 2013). Valiant’s model, PAC learning, provides a broad guarantee that we can build a statistical model capable of discriminating instances of a target distribution (or “concept” in machine learning). The nature of that guarantee is that, with enough exposure to training samples, we can select a hypothesis with low generalization error (the “approximately correct” part), with high probability (the “probably” part). PAC learning formally underlies many, but not all, “supervised” learning methods in statistics and machine learning, including much regression modeling and various classification and pattern recognition methods.

Intentional Behavior and Learning Theories

But PAC learning is not a “universal” learning theory, as Valiant notes. The basic PAC learning model applies to situations where:

- The learner receives access to data, in the form of measurements of some number of features or covariates, and a “label” indicating to which model or target class that set of covariates belongs

- The label given can be taken as accurate, and not associated with noise or error

- The learner does not direct the generation of the data, but accepts labeled examples as given

As Valiant describes in his book, this kind of process doesn’t directly underlie most examples in genetic evolution. PAC learning, self-evidently, does underlie some types of cultural learning, since of course it (and the statistical algorithms that implement it) are cultural constructions by humans, to aid in understanding complex aspects of their environment.

But the framework is too restrictive to cover all learning in cultural contexts, and thus most of the ways in which humans formulate intentions for action on the basis of information gathered. In fact, each of the restrictions above can be relaxed, and in doing so, result in different learning models.

In discussing the relation between learning theory and biological evolution, Valiant correctly focuses upon relaxing the first requirement: that the learner see the detailed data. One way to frame biological fitness within learning theory is to treat classes of genomes as “queries” that populations make into the environment, which responds with summary data: average length of survival, average number of offspring for individuals with that class of genome. The population evolves by aggregating this feedback in the form of differential persistence of seemingly successful phenotypes.

The leaning framework just described is a modification of PAC learning by Kearns called “statistical query learning” (Kearns 1998), and while the interpretation of fitness as statistical queries against the environment might sound like a bit of a stretch, there are many behavioral contexts which fit such a model nicely. Individuals learning a skill, for example, might make attempts and observe the results, and modify their next attempt accordingly. Rarely will individuals have detailed information about the various contributing factors leading to the outcomes, especially in a complex activity such as hunting or making stone tools. Moreover, the same actions and tools may lead to differing outcomes on different trials, leading to only summary information about the outcome of an action or tool on average.

But humans do more than simply learn by aggregating data; we can guide the process of data collection and learning to improve performance. In situations where we can make trials, and then consult an “expert” for feedback, we can tune our next trial based upon the feedback, and repeat the loop. Much of human learning and the entire “apprenticeship” model for learning complex skills is based on this kind of model. In formal terms, this is “active learning,” which is the subject of quite active study within machine learning and statistics (Jamieson, Jain, and Fernandez 2015). Of particular interest is a recent NIPS conference paper which studied active learning when learners have access to both “strong” and “weak” labelers. A strong labeler is very accurate at providing feedback, but expensive to consult, weak labelers are cheap to consult but are occasionally inaccurate. Examples of each in a human context might be asking the master craftsman for feedback rather than students slightly more advanced than oneself, or hiring a skilled attorney rather than Googling for an answer. Zhang and colleagues find, of course, that there are situations where consulting a mix of strong and weak experts can result in highly accurate learning (Zhang and Chaudhuri 2015). This should be unsurprising, because the essential features of multiple-oracle active learning are in play in most human learning environments (e.g., schools, medical residency programs, craft apprenticeships, legal associate programs, and so on).

Furthermore, learning models must account for structured information. The learning task is rarely simply to recognize or predict a single type of distribution or concept, but instead is multi-stage, with stages building upon one another. Real knowledge has prerequisites, and structure, and we can easily fail to learn a skill if we do not yet have a solid grounding in the information and skills that come before. This will have marked effects on our cultural transmission models, and require close collaboration with learning theorists, but should yield much richer analyses of technological change in particular (Madsen and Lipo 2015).

Finally, only occasionally do we learn in a focused way where we are regularly getting labeled feedback, from whatever source. Much of our learning about the world comes in a combination of data points, some of which come with feedback, and much of which doesn’t. Such situations fall within so-called “semi-supervised” learning. Or, we get batched feedback, where we get a single evaluation for a number of different trials which may vary in subtle ways (Settles, Craven, and Ray 2008). Finally, we often learn not by exploring an entire space of possibilities, but by actively looking for the most “informative” or representative portions of that space of examples (Huang, Jin, and Zhou 2010).

Discussion

The basic point is that many variations on statistical learning models will be applicable in understanding how humans learn, both from the environment and by cultural transmission and teaching. Note, however, that in none of the models does the learner understand the ultimate consequences of incremental steps. Even in active learning models where the learner can take past knowledge to query for specific and informative data samples to guide future action, the progress in accuracy is local and stochastic; overfitting is still a concern and it is still impossible to know ahead of time what the ultimate “generalization error” of one’s strategies will be.

Cultural evolution is, undoubtedly, a mixture of intentional and unintentional processes, of unthinkingly copying someone else but also deeply studying carefully chosen mentors and experts. There is room in our theories of cultural evolution for pure diffusion processes that look very much like epidemiological or simple population genetic models, and processes that draw deeply from cognitive science, childhood development, and rich ethnography for their details. There is even room for the subtle combinatorial cognitive processes that lead to “creativity” and true invention.

All of these, and more, are understandable without exiting the Darwinian paradigm, and various theories of statistical learning promise to play a large role in extending Darwinian evolution to those intentional processes. But intentionality, like creativity, are not a sign that natural selection cannot act on culture, or that culture is not Darwinian. The latter is a continuing misconception that largely stems from overinterpreting what “random variation” means in the evolutionary context.

References Cited

Eerkens, J.W., and C.P. Lipo. 2005. “Cultural Transmission, Copying Errors, and the Generation of Variation in Material Culture and the Archaeological Record.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 24 (4). Elsevier: 316–34.

Gabora, Liane. 2013. “An Evolutionary Framework for Cultural Change: Selectionism Versus Communal Exchange.” Physics of Life Reviews 10 (2): 117–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2013.03.006.

Huang, S J, R Jin, and Z H Zhou. 2010. “Active learning by querying informative and representative examples.” Advances in Neural Information …. http://papers.nips.cc/paper/4176-active-learning-by-querying-informative-and-representative-examples.

Jamieson, K G, L Jain, and C Fernandez. 2015. “NEXT: A System for Real-World Development, Evaluation, and Application of Active Learning.” Advances in Neural …. http://papers.nips.cc/paper/5868-next-a-system-for-real-world-development-evaluation-and-application-of-active-learning.

Kearns, Michael. 1998. “Efficient Noise-Tolerant Learning from Statistical Queries.” J. ACM 45 (6). New York, NY, USA: ACM: 983–1006. https://doi.org/10.1145/293347.293351.

Kearns, Michael J, and Umesh Virkumar Vazirani. 1994. An Introduction to Computational Learning Theory. MIT press.

Madsen, Mark E., and Carl P. Lipo. 2013. “Saving Culture from Selection: Comment on an Evolutionary Framework for Cultural Change: Selectionism Versus Communal Exchange, by L. Gabora.” Physics of Life Reviews 10 (2): 149–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2013.03.008.

———. 2015. “Behavioral Modernity and the Cultural Transmission of Structured Information: The Semantic Axelrod Model.” In Learning Strategies and Cultural Evolution During the Palaeolithic, edited by Alex Mesoudi and Kenichi Aoki, 67–83. Replacement of Neanderthals by Modern Humans Series. Springer Japan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55363-2_6.

Power, Daniel A, Richard A Watson, E rs Szathm ry, Rob Mills, Simon T Powers, C Patrick Doncaster, and Blazej Czapp. 2015. “What can ecosystems learn? Expanding evolutionary ecology with learning theory.” Biology Direct, December. Biology Direct, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13062-015-0094-1.

Settles, B, M Craven, and S Ray. 2008. “Multiple-instance active learning.” Advances in Neural Information …. http://papers.nips.cc/paper/3252-multiple-instance-active-learning.

Valiant, Leslie. 2013. Probably Approximately Correct: Nature’s Algorithms for Learning and Prospering in a Complex World. Basic Books.

Wilson, David Sloan. 2016. “Intentional cultural change.” Current Opinion in Psychology 8 (April): 190–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.12.012.

Zhang, C, and K Chaudhuri. 2015. “Active learning from weak and strong labelers.” Advances in Neural Information Processing …. http://papers.nips.cc/paper/5988-active-learning-from-weak-and-strong-labelers.

| Back to Essay List | Modified: 23 Jul 2020 | BibTeX Entry | RIS Citation |

Tags