Semantic Axelrod with Concept Trees and Graphs

| Created: 11 Dec 2013 | Modified: 17 Jun 2014 | BibTeX Entry | RIS Citation |

Extensible Trait Models

An “extensible traits” version of the Axelrod model is complete,1 in which there are no loci or features, but individuals hold any number of traits. If differs slightly from loci/allele models in that none of the traits are mutually exclusive alternatives, so we can also think of it as a single locus model with multiplicity and no exclusion.

The model also initializes agents with a variable sized set of traits, which can grow via a stochastic, “mutation” like process; each model run is parameterized with an addition probability which determines how often a copied trait replaces an existing trait, or is simply added to the agent’s trait set, growing its size.

The copying rule is a modification of the basic Axelrod rule, and assumes that agents hold traits in a Set class (rather than list, etc). Agents interact with a probability determined by the overlap in trait sets, which in sets of variable size is simply the Jaccard coefficient. Interaction also does not occur if the neighbor’s trait set is a strict subset of the focal agent’s traits, since there are no “new” traits to adopt. In pseudocode:

if agent == neighbor or agent.isdisjoint(neighbor) or neighbor.issubset(agent):

return

else:

prob = len(focal.symmetric_difference(neighbor)) / len(focal.union(neighbor))

if draw(prob) == True:

traits = neighbor.get_differing_traits(agent)

neighbor_trait = random.choice(traits)

if draw(addition_rate) == True:

agent.add(neighbor_trait)

else:

agent.replace_random_trait_with(neighbor_trait)Otherwise, the model remains the same. Each run proceeds until convergence, measured as the lack of “active” links.

The point of this model is twofold. First, it serves as essential infrastructure for later semantic models, allowing a variety of trait structures that do not employ the locus/allele formalism. Second, since copying is still random with respect to individuals and traits, the extensible model serves as a neutral “null model” for comparison to later models.

Informally, the extensible model displays the same gross behavior as an Axelrod model with a small number of features and small to moderate number of traits, i.e., typically it converges to the monocultural state but occasionally to a multicultural state with a small number of distinct cultures (usually represented by single nodes).

Semantic Trees

The first semantic model I constructed uses a single balanced tree of traits, mainly in order to bootstrap the infrastructure. The idea is that trees are useful for describing situations where concepts or traits have ordered relations such as being prerequisites for one another. In such a model, an agent would be able to adopt concept X only it already possessed the prerequisite concepts for X – i.e., those concepts along a graph path between concept X and the root of the tree.

Such a population is initialized by generating random partial paths within the tree, which need not span to the leaves. Simply embedding this structure in an extensible trait model is insufficient, however, since the presence of the root node in each agent’s trait set would guarantee eventual monocultural convergence – there could be no disjoint cultures. So additional structure is needed.

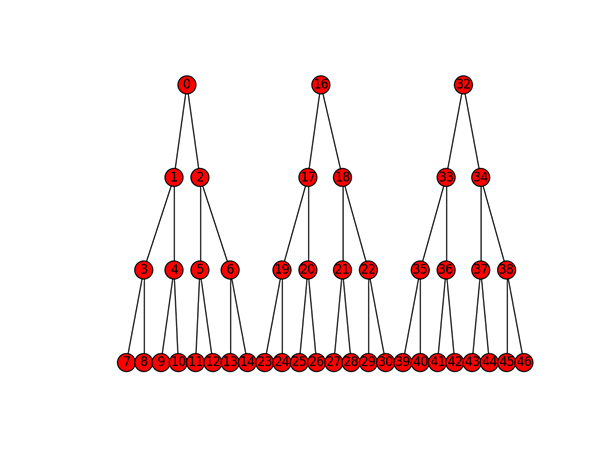

The next step was to construct a trait model with multiple trees, each of which has the same topology (although this is necessary only in one method, for calculating the number of nodes). Each of the trees lives in the same graph object, so lookups and path calculations work. The overall graph simply is disconnected, with N connected components, where N is the number of trees. Each tree would represent a realm of related concepts, with prerequisite relationships between nodes in a given tree. And monocultural convergence is not guaranteed, although everyone in a given “culture” is guaranteed to have the same set of root nodes and leaves, albeit from possibly non-overlapping sets of trees. An example of a balanced multi-tree structure is:

Initialization

As an example of initializing a population, imagine initializing 8 trait trees, with branching factor 3 and depth 3. This yields roots at [0,41,82,123,164,205,246,287]. If we then take random paths through trees chosen at random, we get something like the following:

[123, 125, 132, 152]

[82, 84, 89]

[164, 167, 176, 202]

[287, 289, 296, 315]

[123, 126, 134, 157]

[0, 3, 10]

[205, 207]

[82, 83, 86, 95]

[82, 85, 93, 117]Interaction with Prerequisites

Given trait sets which are structured as “chains of concepts,” the extensible Axelrod interaction rule can be generalized such that individuals may only “adopt” traits (and thus come to possess the relevant knowledge or information), when they already have appropriate prerequisites skills or knowledge. In this example, we deal only with terminal or “leaf” traits, although copying rules which are more complex are possible, see below.

As an example, at a given step in the simulation, Agent A is selected as the “focal” individual, and Agent B as a random neighbor of A. Let us imagine that we calculate the overlap between their trait sets, and a random draw shows that they interact this time step.

In Case 1, when we look at any of the trait chains, the focal agent cannot “learn” trait 157from the neighbor. Even though they share [123, 125] as basic knowledge, they differ between 132 and 134.

Case 1: Lacking Prerequisite

# Agent A

([123, 125, 132, 152],

[82, 84, 89],

[164, 167, 176, 202])

# Agent B

([287, 289, 296, 315],

[123, 125, 134, 157],

[0, 3, 10])In contrast, in Case 2, the focal agent can “learn” trait 157 from its neighbor. The focal agent and the neighbor share the prerequisites needed for both 152 and 157, namely the chain [123, 125, 132]. In the simplest rule, the focal agent replaces its leaf trait with the neighbor’s.

Case 2: Has Prerequisite, Replaces Trait

# Agent A

([123, 125, 132, 152],

[82, 84, 89],

[164, 167, 176, 202])

# Agent B

([287, 289, 296, 315],

[123, 125, 132, 157],

[0, 3, 10])Case 3: Has Prerequisites, Adds Knowledge

In Case 3, we implement the “addition rate” from the “extensible trait” model above, and allow the focal agent to add the neighbor’s trait to their own if prerequisites occur. Given such an event, after interaction, we now have:

# Agent A

([123, 125, 132, 152],

[123, 125, 132, 157],

[82, 84, 89],

[164, 167, 176, 202])

# Agent B

([287, 289, 296, 315],

[123, 125, 132, 157],

[0, 3, 10])This is a simple way of representing the trait set, but 132 is also just a branch point in the tree, and we have [123, 125, 132, [152, 157]]. The representations are equivalent, so the choice is about computational efficiency.

Random Trees and Graphs

Balanced trees are an excellent way to build out the simulation infrastructure, but they clearly represent one highly ordered endpoint to modeling knowledge relations (and a very unrealistic one).

Real knowledge and skills are going to vary in their depth and branching factors, and thus we should expect non-regular tree topologies, which might be best modeled by appropriate collections of power-law trees. This is an experiment TBD.

Other types of relations beyond prerequisites exist, and we may wish to simply use random graphs to model combinations of prerequisites, related information, background knowledge, and so on. This again is an experiment TBD.

References Cited

All code in this project is open source and located in Github.↩